When I talk about growing up with computers, and my early programming days of my childhood, I usually recall fond memories of the Commodore VIC-20 and Commodore 64. But the truth is, my first computer was the Timex Sinclair 1000.

When I talk about growing up with computers, and my early programming days of my childhood, I usually recall fond memories of the Commodore VIC-20 and Commodore 64. But the truth is, my first computer was the Timex Sinclair 1000.

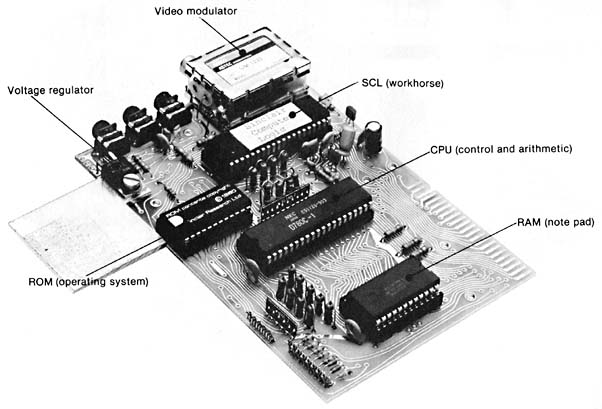

The one pictured here has the 16KB RAM expansion module. I had nowhere near the money to buy that at 12 years old, so the one I had contained the standard 2KB of RAM, and the BASIC programming language built into ROM. So I had basically 2KB to work with.

It also had a membrane keyboard and common BASIC programming language commands like GOTO and GOSUB could be entered by just pressing one key. These computers were TINY, much smaller than anything out today, and weighed just 12 ounces. They had a Zilog Z80 CPU that ran at 3.25Mhz, and video output using an RCA video connector to hook up to a TV where it displayed text only at 22×32 resolution. There were no disc drives available for it, so you had to store the programs that you wrote or bought on cassette tapes using a standard tape player, or in my case, a ghetto blaster.

This worked more or less, as long as you turned the treble way up, and the bass way down. You did tend to lose a lot of work, but it was better than nothing. The Timex Sinclair 1000 is the North American version of the Sinclair ZX-81, from British based Sinclair Research Ltd. They are nearly identical, except for the name on the front, and minor motherboard layout differences. The first Sinclair computer was the ZX-80, released in 1980 for $200.00. It was still very popular when they came out with the improved ZX-81 in 1981. By mid-1982, Timex was selling the ZX-81, renaming it as the ‘Timex Sinclair 1000’.

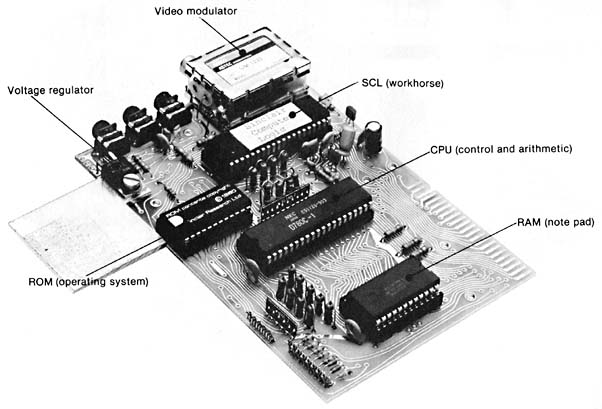

The motherboard of the Sinclair 1000 had only 4 Integrated Circuit chips, including the Z80 CPU. It would have been easy for even a kid to build from a kit, but Timex never offered the Sinclair 1000 in kit form, though it’s predecessor, the ZX80, could be bought in kit form for a $20 savings.

The motherboard of the Sinclair 1000 had only 4 Integrated Circuit chips, including the Z80 CPU. It would have been easy for even a kid to build from a kit, but Timex never offered the Sinclair 1000 in kit form, though it’s predecessor, the ZX80, could be bought in kit form for a $20 savings.

The rest of this entry is from BYTE magazine, the January 1983 issue.

The Timex/Sinclair 1000

Billy Garrett

POB 18806

Greenboro, NC 27419-8806

Many BYTE readers own a personal computer, just as I do. And like many readers, I justify the cost of the computer by using it for word processing, mathematical programs, job-related applications, and even games. But if you’re as addicted to computers as I am, you will eventually do something that you may never be able to explain – buy another one.

Sure, I could easily explain such a purchase if my old computer was too slow or unable to do the things that the new one could, but that’s not the case at all. That excuse is reserved for some 16- or 32-bit processor that isn’t on the market yet. The fact is I suddenly found myself buying a Timex/Sinclair 1000. And what’s worse, I already own a Sinclair ZX80! Clearly, this was going to take some creative explaining.

At first, I thought I could convince people that I bought it for experimentation, but that argument is a little shaky. I concluded that the only way to justify the purchase was to write a review of it.

As most of you know, the Timex/Sinclair 1000 is essentially the same as the Sinclair ZX81. What you might not know is that all along Timex has been building the ZX81 for Sinclair. Under either name, the Sinclair people seem to have outdone themselves in designing it. It is similar to the older ZX80, and ZXSO users can upgrade their computers to the full capabilities of a T/S 1000.

In this review, I will first give you a general idea of what the unit is like. I’ll then take you on a trip through the inner workings of the hardware. Finally, I’ll try to compare the BASIC interpreter against some known standards. When I’m finished, I hope you’ll see why the T/S 1000 fascinated me, and why I bought one.

General Characteristics

The T/S 1000 comes completely assembled and tested for $99.95. At one time, if you wanted to save $20 and spend a few hours assembling a computer, you could have ordered the Sinclair ZX81 kit. But Sinclair has now stopped selling the ZX81 and has allowed Timex an exclusive market in the United States. You can expect the new Sinclair Spectrum color computer to be handled in the same way. Sinclair will sell them exclusively for a while, and Timex will then take over the marketing.

The basic T/S 1000 package consists of the unit shown in photo 1 plus patch cords for a recorder, a connection wire and switch box for your TV, a manual, and a transformer. An optional 16K-byte RAM (random-access read/write memory) pack is also shown in photo 1.

The computer is easy to set up and use. Clear instructions show you what to do, and practically anyone should be able to set the computer up quickly. The accompanying manual is well written. Although it is not too simplistic, people with no knowledge of computers will be able to read it.

The T/S 1000 must of course be hooked up to a television set to be useful. The display, made up of black characters on a white background, has 24 lines with 32 characters per line. The two bottom lines, however, are used by the BASIC interpreter. Therefore, you really have only 22 lines. Within the character set are several graphics characters that are useful for games and charts, The cursor on the screen acts as a prompt and appears ar a reverse video K, L, F, G, or S, which shows how the computer is going to interpret the next key entered. It will be interpreted as either a keyword, a letter (or number or symbol), a function, a graphics symbol, or a letter to correct a syntax error (if you make one, that is!).

| Photo 1: The Timex/Sinclair 1000 computer with the optional 16K-byte RAM pack, which attaches to a connector on the right rear of the computer. The basic unit powers the RAM pack. (Photo courtesy of Timex Computer Corporation.) |

The cassette interface is simple and reliable. You can name programs when you save them, and have the computer search through the tape and find a specific one, or just load the next one found.

The most restricting thing about the computer is the keyboard. I am used to typing, and it is impossible to type on a keyboard as small as this one. Also, each key can signify up to four things (a letter, a BASIC keyword, a function, or a graphics symbol). Although the keys are well marked, it is hard to remember which key does what. Some of the keywords, like Delet’e and Edit, are in awkward places. The keys themselves provide almost no tactile feedback and are closely spaced; you constantly have to look at the screen to see if you have pressed the right key.

At A Glance

Name

Timex/Sinclair 1000

Manufacturer

Timex Computer Corporation

POB 2655

Waterbury, CT 06725

(203) 574-3331

Price

$99.95

Dimensions

6 5/8- inches wide by 7 inches long by 1 1/2-inches high (16.8 by 17.7 by 3.9 cm)

Processor

Z80A, 8-bit, 3.25-MHz clock frequency

Memory

2K-byte RAM standard; 16K-byte RAM optional ($49.95); 8K-byte ROM included

Mass Storage

Cassette I/O, only program storage and loading; no BASIC controlled I/O

Display Used

Standard television set (RF modulator included); 32 black-and-white characters per line,

24 lines; the user cannot use the bottom two lines, which are reserved for the BASIC interpreter’s use

Other Features

Membrane keyboard; built-in modulator (for TV); includes ail cables and transformer

Documentation

l54 pages, spiral-bound manual

Software Included

BASIC in ROM

Software Options

Various application programs avaitable on cassette

Hardware Options

16K-byte RAM ($49.95);

electrostatic printer ($99.95);

telephone modem ($99.95)

Audience

Students, businesspeople, or anyone else interested in learning about computers for a very low cost |

Also, although it’s hard to use the keyboard as you would a typewriter, it is not very easy to use as a calculator either. Most calculators have a Function key that accesses a function written above certain keys. With a calculator, you just press the Function key and then the key you want. The Shift key on the T/S 1000 serves the same purpose, but you must hold it down while you press the key you want. This means you have to use two hands. It would be easier if the Shift key could be used as on a calculator.

T/S 1000 BASIC is fairly easy to use. BASIC keywords can be entered with just one keystroke, but that’s the only way these keywords can be entered. Line numbers from 1 to 9999 can be used. Multiple statements per line are not allowed. Error codes and program lines start on the bottom two lines of the display and work their way up the screen. Because the error codes are displayed as numbers, you will have to look them up in the manual to see which error occurred.

A nice feature is that the names of most variables can be any length. LONGNAME and LONGNAME2 are different and distinct variables. The T/S 1000’s string- handling capabilities are nonstandard, as will be explained later. All things considered though, T/S 1000 BASIC is powerful.

Finally, the T/S 1000 has a 90-day warranty, which should help most users if they find out that their computer is actually a lemon. Timex also offers a one-year extended warranty for $12. This offer is good only for people whose warranty hasn’t run out, or those who have just had their unit in for repair. Timex even provides a computer club, open to all T/S 1000 owners, that will keep them up to date on any new developments, hardware and software products, and special offers. One last thing, because the T/S 1000 is being marketed everywhere, a good shopper can probably find it for a bit less than $99.95. I haven’t even looked hard and I’ve seen it for $87.

The Insides: The Less, The Better

The T/S 1000 uses state-of-the-art circuitry. Only four ICs (integrated circuit chips) are inside the small enclosure, as is shown in photo 2. These four ICs, along with an IC voltage regulator; two transistors; several diodes, resistors, and capacitors; a video modulator; and the membrane keyboard, make up the entire unit. One big change between the ZX80 and the T/S 1000 (ZX81) is a custom 40-pin IC made by Ferranti (a large British semiconductor manufacturer), which replaces 18 ICs that were in the ZX80 and adds additional logic circuitry. This chip is called the SCL (Sinclair Computer Logic). The new logic circuitry inside the SCL allows the T/S 1000 to display a picture continuously on the TV, even when the computer is executing a program. This is a big improvement over the older ZX80 that couldn’t display a picture while executing a program; the screen would go blank every time a program was run or any time you pressed a key.

Photo 2: The small circuit board inside the Timex/Sinclair 1000. Note that in this photo some of the chips have been put in backward so that you could read what’s on top. The silver plate on the bottom left side is the heat sink. The connector in the right rear is for expansion. The three jacks on the left side are for power, tape in, and tape out. The two small connectors that are part of the right front of the board are where the keyboard is connected. The other parts are clearly labeled. (Photo courtesy of Timex Computer Corporation.) |

The Microace company sells a modification for the ZX80 that allows a ZX80 owner to have the equivalent of a T/S 1000. Unfortunately, although the additional logic board is small and contains only seven ICs, the board won’t fit inside the ZX80’s case. But if you really want the continuous display, the upgrade is only $29.95 from Microace (see table 1). It works fairly well, but the board is not made by Sinclair, and I had problems with it. Microace was prompt in responding to my request for help, but its response was that I must have assembled something wrong or that something wasn’t working properly. The latter turned out to be the case. After I replaced a 74LS00 chip, the modification board worked fine.

The basic T/S 1000 unit comes with 2K bytes of static RAM (random-access read/write memory). This is the only difference between it and the Sinclair ZX81; the ZX81 had only 1K bytes. In either case, this is hardly enough to do any serious programming because the display shares this RAM with the program. A program that fills the TV screen will quickly run out of display room when the program is run. The BASIC interpreter uses 124 bytes of the RAM for its own internal processing, and the display can occupy a maximum of 727 bytes of memory. That leaves 173 bytes for a program in the ZX81 and 1197 bytes in the T/S 1000. Of course, because the display is not hard-mapped to one location in memory, it occupies only as much memory as it really requires.

In addition to the RAM, there is an 8K-byte ROM (read-only memory) chip in which the character generator for the display and the BASIC interpreter reside. The character generator occupies about 512 bytes of the ROM; the rest is used for the BASIC interpreter and the I/O (input/output) procedures.

The central processing unit not only has to execute the BASIC interpreter, but also must handle the TV display. This is accomplished through a clever arrangement. After each instruction is fetched from memory and executed, the display circuitry accesses the ROM and loads the bits

| Information on the flicker-free board for the Sinclair ZX80:

Microace

1348 East Edinger

Santa Ana, CA 92705

(714) 547-2526

Monthly newsletter:

Syntax

The Harvard Group

RR 2, Box 457

Harvard, MA 01451

(617) 456-3661

Bimonthly magazine:

SYNC (Published by Creative Computing)

39 East Hanover Ave.

Morris Plains, NJ 07950

(201) 540-0445

Schematics, etc.:

Heuristics

25 Shute Path

Newton, MA 02159

Table 1: The addresses of some companies that might be of interest to owners of the Timex/Sinclair 1000 or the Sinclair ZX81. |

of the character to be displayed on the screen. The bits are then serialized and sent to the TV with that custom-made 40-pin logic chip. The processor must coordinate this activity, which requires a lot of its time. Because of this, the T/S 1000 offers two modes of operation available to the user: SLOW and FAST. When the unit is turned on or when a NEW command is executed, the display enters the SLOW mode. This means that the display is on continuously, even during the execution of a program. If you do not need to have the display on all the time, you can use the FAST mode. In this mode, the display is on only when a program has finished running or when the unit is awaiting input. The manual states that the difference in execution speed of the two

modes is a factor of about four, but in every test that I have run the difference is almost a factor of six. I haven’t run any benchmark programs, but even in the FAST mode this is about the slowest BASIC interpreter I have ever used.

The design of the circuit board is interesting. The current revision has provisions for different types of RAM chips to be plugged into the board. The ZX81s came with two 2114 chips, for a total of 1K bytes. The T/S 1000 uses a single 2K-byte RAM chip. When you need more memory, you can buy the 16K-byte RAM pack for $49.95.

One of the most exciting things about the T/S 1000 circuit is that the ROM socket was designed so that larger-capacity ROM chips could be plugged in. If you are familiar with the standard ROM pin arrangements, you know that with a 24-pin package the maximum size of a standard, nonmultiplexed, byte-wide ROM chip is 8K bytes. Well, Sinclair has already wired the board for a 28-pin package, which would allow a 16K-byte ROM chip. Although Sinclair has not commented on the possibility of a 16K-byte ROM for the T/S 1000 or its successor, you can be sure that someone is thinking about it. A 16K-byte ROM would increase the capabilities of the T/S 1000 greatly, but it may be a while before we hear anything about that possibility.

Unlike the keyboard in the ZX80, the T/S 1000 keyboard is not an integral part of the main circuit board. It thus can be easily replaced, and Sinclair could design a more conventional “full-travel” keyboard and offer it as a replacement. I, for one, would like a better keyboard; and with more than 200,000 T/S 1000s and ZX81s in existence, Sinclair stands to make lots of money on any good accessories. Current plans, however, include only a printer and a modem.

T/S 1000 BASIC

The new 8K-byte BASIC included in the T/S 1000 is remarkably powerful for being just 7.5K bytes long (remember that the character generator occupies 512 bytes of ROM). Tables 2 through 5 list all the available commands, while table 6 includes some commands that are common for BASIC but not implemented in this version.

| Function |

Type of Operand (x) |

Result |

| ABS |

number |

Absolute magnitude |

| ACS |

number

(-1 <= x <= 1) |

Arc cosine in radians |

| AND |

binary operation

AND |

A AND B

= A (if B0)

= 0 (if B = 0) |

| ASN |

number

(-1 <= x <= 1) |

Arc sine in radians |

| ATN |

number |

Arc tangent in radians |

| CHR$ |

number (0 to 255) |

The character associated with a given code |

| CODE |

string |

The code of the first character in string (or 0 if x is the empty string) |

| COS |

number (in radians) |

Cosine |

| EXP |

number |

Exponential function (ex) |

| INKEY$ |

none |

Scans the keyboard once and returns the character if a key is pressed or returns the empty string if no key is pressed |

| INT |

number |

Integer part (always rounds down) |

| LEN |

string |

Length of string |

| LN |

number (x >= 0) |

Natural logarithm |

| NOT |

number |

NOT x

=0 (if x 0)

=1 (if x=0) |

| OR |

binary operation |

A OR B

=1 (if B0)

=A (if B=0) |

| PEEK |

number

(0 <= x <= 65535) |

The value of the byte in memory whose address is x |

| PI |

none |

3.14159265 |

| RND |

none |

The next number in a pseudorandom sequence of 65,535 numbers |

| SGN |

number |

Sign of the number ( – 1, 0, 1) |

| SIN |

number (in radians) |

Sine |

| SQR |

number (x => 0) |

Square root of x |

| STR$ |

number |

The number x returned as a string |

| TAN |

number (in radians) |

Tangent |

| USR |

number

(0 <= x <= 65535) |

Calls the machine-code subroutine whose start address is x; on return, the result is the contents of the BC register pair |

| VAL |

string |

Evaluates the string as a numerical expression |

| “-“ |

number |

Negation |

| Table 2: Some of the functions found in TlS 1000 BASIC. |

| Symbol |

Operation |

| + |

addition |

| – |

subtraction |

| * |

multiplication |

| / |

division |

| ** |

raising to a power |

| = |

equals |

| > |

greater than |

| < |

less than |

| <= |

less than or equal |

| >= |

greater than or equal |

|

not equal |

Table 3: The binary operations

included in TS/1000 BASIC. |

The manual does a good job explaining the language, and it is interesting to note how this manual was developed. First, there was a British version for the Sinclair ZX81, which naturally tended to use British colloquial expressions. That manual was much more interesting than the subsequent American Sinclair or Timex versions, although all are equally informative. For example, at one point the author of the British version refers to photo 2 and writes, “As you can see, everything has a three letter abbreviation (TLA).” I thought this was a rather amusing comment, and most of the examples are humorous also. This is a good way of making the novice feel a little more relaxed while he or she is trying to learn what all those darn abbreviations are for. Unfortunately, the humor was carefully excised from the American manuals, even though the manuals are exactly the same in content and number of examples. Any one of these manuals, however, is an excellent introduction to BASIC. The many examples and exercises should make it easy and fun to learn.

The manual is mostly devoted to BASIC, but it also covers some rather intricate details of the BASIC interpreter. One interesting point about the manual is that it not only tells you which bytes in memory are used, but also what they are used for. This documentation is helpful if you are going to write any machine-language routines. This is a useful piece of information for them to include, something that many other companies can’t or won’t do because of their agreements with the authors of their BASIC interpreter.

T/S 1000 BASIC does differ substantially from the Microsoft variety that many of us are acquainted with. This BASIC was apparently written by a group of Cambridge (England) mathematicians. The biggest improvement that this 8K-byte ROM has over the 4K-byte ROM that was standard in the ZX80 is that this version handles floating-point numbers. Also included are the usual functions, such as SIN, COS, and LN, that are standard with most BASICs. This version, however, suffers from one really bad problem – string irregularities.

Most people who have used BASIC are accustomed to string functions like LEFT$, RIGHT$, MID$, or other functions like these. For example, LEFT$(NAME$) allows you to examine the first letter of a name. But the T/S 1000 uses what they call slicing notation. A few examples will clarify this immediately:

LET A$ = “SINCLAIR”

PRINT A$(1 TO 8)

would print: SINCLAIR

PRINT A$(3 TO )

would print: NCLAIR

PRINT A$(1 TO 1) + “ILLY”

would print: SILLY

| Command |

Function |

| AT |

Used in a PRINT statement to specify the position of the cursor. |

| CLEAR |

Deletes all variables, freeing the space they occupied. |

| CLS |

Clears the display file. |

| CONT |

Continues if the program has any executable lines left. |

| COPY |

Copies the contents of the screen to the printer. The COPY command will not change the display. |

| DIM |

Reserves enough memory for an array of the given dimension and deletes any arrays already set up with that name. |

| FAST |

Increases execution speed by turning the display off when a program is running. |

| FOR a = x TO y STEP z |

Executes a FOR/NEXT loop and deletes any other variable that will conflict with the loop variable a; will count from x to y by increments of z. |

| GOSUB |

Pushes the line number of the GOSUB statement on a stack and calls the BASIC code starting at that line number. |

| GOTO |

Jumps to the specified line or the next one after that number. |

| IF exp THEN s |

If exp is true, then s is executed, and s must be a statement. |

| INPUT v |

Stops and waits for the user to input an expression. |

| LET |

The variable assignment statement. |

| LIST |

Lists the program on the screen. |

| LLIST |

Same as LIST, except that it goes to the printer. |

| LOAD f |

Loads a program called f. Loads the first program if f is null. |

| LPRINT |

Same as print, except routed to the printer. |

| NEW |

Deletes any program lines and variables, setting aside all memory up to the top of available RAM or to the system variable RAMTOP, whichever is lower. Also enters the SLOW mode. |

| NEXT |

Ends a FOR loop. |

| PAUSE n |

Stops computing and displays the display fiie for n frames (at 60 frames per second) or until a key is pressed. |

| PLOT x,y |

Blacks in pixel x,y and moves the print position one space to the right of that pixel (resolution: 64 by 44). |

| POKE m,n |

Replaces byte at location m in memory with byte n. |

| PRINT |

Prints whatever you specify in the print statement on the screen. |

| RAND |

Seeds the random-number generator. |

| REM |

Makes that line a comment statement, which is ignored by the computer. This is useful for placing machine-language subroutines in REM statements since they don’t move about in memory. |

| RETURN |

Pops the number from the GOSUB stack and returns to the line after it. |

| RUN |

Runs a program beginning with the line you specify, or the beginning if you don’t. |

| SAVE |

Saves the program, variables, and other system information on tape. |

| SCROLL |

Scrolls the display file up one line, replacing the bottom line with a NEWLINE character. |

| SLOW |

Leaves the display on all the time, even during the program execution. The computer powers up in this mode and returns to the SLOW mode whenever a NEW command is executed. |

| TAB |

Prints at this position, Must be used in a PRINT statement. |

| UNPLOT x,y |

Whitens out the pixel x,y. |

As you can see, the slicing notation takes the number of characters that you specify in the range given in parentheses and prints them. If the first or last number is left off, it assumes the beginning or the end of the string respectively. This is not at all hard to get used to, but it is nonstandard.

One really good feature is that the strings can be any length, but string names are limited to one letter followed by the string symbol “$”. You can get more than 26 strings, though, by dimensioning them. When you do so, however, you must specify how many characters are going to be in each string. For example, if you type DIM X$(2,20), you get two strings each with a length of 20 characters. This too is nonstandard for BASIC.

One bad point about the T/S 1000 is its lack of compatibility with the old ZX80 programs (written using the 4K-byte ROM). The programs will run, of course, but the user must make some minor modifications, type them in again, and save them on cassette tape.

As a cassette-based machine, the T/S 1000 has certain limitations. For example, this BASIC does not allow you to save values of some of the variables without saving all the variables and the program too. In fact, the entire state of the machine is saved when you execute a SAVE command, so that you can get right back where you were after loading the program and typing CONT. This limitation of the SAVE command makes the T/S 1000 difficult to use with programs that require saving data, but it is convenient for the novice. One limitation is that the SAVE command must not be nested inside a GOSUB. Another limitation is that cassette I/O is slow, and the T/S 1000 is not a likely candidate for a floppy-disk interface mainly because of the expense. Certainly, a floppy disk could increase the capabilities of the T/S 1000, but who would buy a controller and disk for $400 when the basic computer was only $100? But we don’t know what Clive Sinclair will be up to next… a microfloppy for $100?

The actual process of entering a program is easy for the novice but exasperating for the experienced computer user, because BASIC keywords can be entered only by using a one-key abbreviation. If you want to enter RUN, you just press the R key and then the NEWLINE key, instead of pressing R, U, N, and then NEWLINE. It will take a while to learn the location of each keyword. Some are in awkward places. The RUBOUT (delete) key is a shifted 0. Frequently, I forget to press the Shift key before I press the 0 key.

| Command |

Function |

| EDIT |

Edits the current line. |

| Up arrow |

Moves the current line back one. |

| Down arrow |

Moves the current line forward. |

| Right arrow |

Moves the cursor forward. |

| Left arrow |

Moves the cursor backward. |

| BREAK |

Stops execution of a program. |

| NEWLINE |

Terminates every line. |

| RUBOUT |

Deletes the last character or keyword. |

| GRAPHICS |

The next keys pressed will be interpreted as graphics symbols. |

| FUNCTION |

The next key pressed will be the function written below the key. |

| Table 5: Editing commands found in T/S 1000 BASIC. |

| AUTO |

LINEINPUT |

| DATA |

MEM |

| DEFSTR |

MID$ |

| DEFINT |

ON ERROR |

| DEFSNG |

ON x GOTO |

| DEFDBL |

PRINT # (to cassette) |

| ELSE |

READ |

| FNDEF |

RESTORE |

| INPUT# |

RIGHT$ |

| LEFT$ |

USING |

Table 6: Some common BASIC commands

missing from T/S 1000 BASIC. |

Like the ZX80, the T/S 10

00 has 40 keys. The keyboard can be accessed in a BASIC program either through an INPUT statement or through the INKEY$ function.

One more nonstandard feature is that the character code set is totally unique to the T/S 1000; it’s not ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange). For example, in ASCII the letter “A” is represented by 41 (hexadecimal); the T/S 1000 refers to the same letter as 26 (hexadecimal). Making this unit into a terminal would take a little hardware and a considerable programming effort.

If you want more information on the T/S 1000, ZX80/ZX81, or the Microace computer (no longer made), see table 1 for addresses of these companies. Also, two other articles on these computers have appeared in BYTE. They are “The MicroAce Computer” by Delmar Searls, April 1981, page 46, and “The Sinclair Research ZX80” by John C. McCallum, January 1981, page 94.

Conclusions

Although T/S 1000 BASIC is different, it is powerful for such a small, low-priced computer. I think that anyone who buys it won’t be disappointed. It does, however, suffer from its lack of standardization and omission of powerful BASIC functions. The TV interface works very well, and the display can easily be read on almost any TV. The membrane keyboard makes the computer difficult to work with for long periods of time. The cassette is easy to use for simple program storage, but it is limited and will hamper many application programs. The major use for this computer will probably be for learning about BASIC or computers in general. The computer itself has limited expansion capabilities, and the keyboard is too small and cramped for any serious work.